- Home

- Katherine Keith

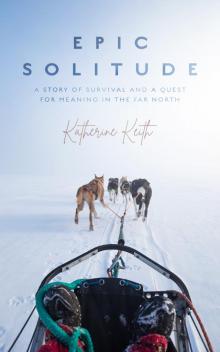

Epic Solitude

Epic Solitude Read online

Copyright © 2020 by Katherine Keith

E-book published in 2020 by Blackstone Publishing

Cover design by Alenka Vdovič Linaschke

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Trade e-book ISBN 978-1-5385-5703-7

Library e-book ISBN 978-1-5385-5702-0

Biography & Autobiography / Personal Memoirs

CIP data for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Blackstone Publishing

31 Mistletoe Rd.

Ashland, OR 97520

www.BlackstonePublishing.com

To Amelia, whose unending faith in me assures me that I can never fail if I keep searching for that next stake.

Introduction

We talk of communing with Nature, but ’tis with ourselves

we commune...Nature furnishes the conditions—

the solitude—and the soul furnishes the entertainment.

—John Burroughs

It is a fall evening above the Arctic Circle in Kotzebue, Alaska. Looking up at a dark sky during a new moon, dazzling stars compete for attention while fire-red northern lights dance in universal celebration. Brought to my knees in surrender of grace, I dream of belonging. I yearn to be part of the symphony of life embodying the perfection of nature, but my song is punctuated with the dissonance of human flaws, of which there are many. Each satellite passing overhead reminds me of loved ones who came into my life before fading out into the horizon. I miss them all.

A falling star burns its way across the sky, making its mark on the Milky Way. That same burning courses its way across my heart, mandating me to tell this story. My story is not unique or heroic. It is raw truth demanding readers as participants to stand in their own authenticity. We have a choice when it comes to how real we get with ourselves and each other. While self-preservation asks us to be nondescript, the fire within demands that we be alive in the fullest sense of the word. That means being vulnerable. I trust you to handle the rawness of life in this book even though it might mean looking into your own pain without blinking.

I grew up in Minnesota in a family full of tradition and with its share of drama but never lacking in love. I sacrificed the security of my family in a gamble on the great unknown. The hunger for the wilderness of Alaska, mountains to be explored, and unexpected journeys requires constant feeding lest I starve. Our souls burn brightly to shed light on this mystery we call life.

Sure enough, life happens along the way. Over marriage, divorce, birth, and death, life gives with surprising ease and takes away with equal ambivalence. When life drags us through the mud of anger, despair, bitterness, and trauma, our tendency is to huddle up and close ourselves off in a defensive posture. We need fireworks to wake us up and open our eyes to the helping hands being offered by those around us. I wrote this book in hopes of being a bright comet to inspire others to open their heart to the possibilities around them even when it hurts the most.

“Life is suffering,” states a major Buddhist precept. In eliminating our attachment to the things and people we love, we may be free from suffering. But what if those attachments give our life purpose? My life—full of attachment, full of suffering—left a mark on my soul. What we do with these scars remains our choice.

As a caterpillar spins a cocoon to become a butterfly, I seek renewal. The vast solitude of the wilderness serves as my cocoon. I enter wilderness quests such as thousand-mile dogsled races and transform each step along the way.

This book details the failures and achievements of a life that I felt compelled to live to the fullest. I may be odd in the way I find connection with the world. Not everyone likes being outdoors in Arctic storms. Not everyone needs a vision quest to uncover past memories. However, we all need the intention of healing in order to guide our lives forward. Wilderness adventures have gifted me with healing. Every life-or-death situation seems to magically parallel some deep trauma that I need to process and release. In facing real-time danger, I gain the courage and confidence to face my far scarier internal demons, the ones we all have.

The path of learning should never end, or we would become stuck in a pattern of limited growth. We have all been there: halfway up the mountain and so tempted to simply stay there, enjoying the view.

We all have the opportunity to become something greater than we have imagined for ourselves. In reading my story, I ask you to consider your own suffering and what can be created from it. What is your cocoon? I’m here to tell you it is not good enough to hang out halfway up the mountain in a bivy sack, suspended from any progress, forward or backward, waiting for an avalanche to take you away into a dark, cold abyss. Try. Take one small step forward, through the pain, suffering, grief, anger, shame, and everything else convincing you that you can’t make it. Life is worth saying yes to.

I turned forty this year. What do I want to do now that I am over the hill? I want to keep climbing and hold the hands of others making their own journey up their mountain of suffering. You are not alone.

Part One:

Starting Line

Iditarod, Mile 777

Unalakleet, Alaska | 2014

Life is either a daring adventure or nothing.

—Helen Keller

When it comes to cold, the crossroads of crisis and necessity is forty-five degrees Fahrenheit below zero. At twenty or even thirty degrees below zero, we can maintain our body temperature so long as we wear the proper gear. But deeper than thirty below, no gear suffices to counteract the cold—not even the four layers on my legs and feet, the six on my torso, the work gloves and two sets of hand warmers inside my musher mitts, and the wool balaclava and liner on my head, all topped off with a goofy-looking beaver-fur hat.

“I’m just a poor boy, nobody loves me,” I sing out, trying to stay awake, to my dogs who march like heroes down the trail. The dogs are used to my off-key singing by now and don’t seemed disturbed by my choice in music.

“Cowboy, take me away. Take me high and above to see the stars,” I cry out, making up the Dixie Chicks lyrics as I go because, despite this being my favorite song, my sleep-deprived brain can’t quite recall the correct words. The dogs don’t seem to mind.

I am seven days and 750 miles into my first Iditarod, the thousand-mile dogsled race across Alaska. I started the race with fourteen dogs and have dropped five at the checkpoints for various reasons. Nine dogs remain with over 250 miles yet to travel.

Just as we leave Unalakleet at forty below zero, the weather service issues a winter storm warning with a high wind advisory. There is only one option: keep moving. We trek over the bare Blueberry Hills rising away from Unalakleet over the Bering Sea. I hope for snow to smooth the way but find none. Covered with sand and rocks and patches of glare ice, the climbs through the hills are long and arduous. After eighteen miles we reach the high point of this section with a steep climb. I scream out in frustration as the dogs slip around on ice while the sled sticks on sand. We cannot move. How are we supposed to do this? Inch by inch, I push the sled forward until the dogs can get off the ice. Their attitudes are positive, and the dogs march on once they get traction.

After about twenty-eight miles we reach the top of the Blueberry Hills, an 850-foot-high view with Shaktoolik visible from twelve miles away. The winds create an effect from the ground storm and combine with the sunset to give the area a glorious golden fog bank. I’ve traveled along enough Arctic coastline to know this fog bank will not be as heavenly to travel through as it appears. I understand how difficult traveling can be between the p

oor visibility, large drifts, glare ice, and low temperatures. But I don’t hesitate, and we start the three-mile descent down into that fog bank at an alarming rate without the ability to stop, careening toward the ground blizzard. A forty mile per hour quartering headwind howls at us from the north, combining with the forty-below temperatures to create a dangerous chill factor of minus eighty-four degrees Fahrenheit.

In bad conditions, twelve miles is a long way to go. The wind and cold take a toll on all of us. Mile after mile, I stand on the footboards of my sled, packed with the minimum of tools and supplies we need to sustain us. My on-sled dance routine consists of kicks, squats, and any other movement I can think of to warm my extremities.

A gust of bitter wind hammers the sled, pushing it sideways off the trail. My grip tightens on the handlebar as I purse my cracked lips together to whistle to the dogs.

“Up! Up!” I yell in a scratchy voice, followed by, “Oh pirates, yes they rob us, soul light to the merchant ships.” I am in my element, having the time of my life. I can sing out, wrong words and all, and there is no one within miles to care.

My team of Alaskan huskies, a cross between the Siberian husky and German shorthaired pointer, run in two lines stretching ahead of me, secured to each other and the sled with dog harnesses. These connect to a gang line, a long cable that attaches the harnesses to the sled.

“I still haven’t found what I’m looking for. What I’m looking for, for, for, for … What I’m looking for,” I sing out as U2 keeps me company in the solitude of this frigid night.

We leave the shelter of trees and bushes behind. The trail follows a slough into Shaktoolik. The lack of snow results in a glass ice rink on the coast. We try to navigate the glare ice, but without traction, the wind pushes the sled sideways off the trail and spins it around the team. Joy and Summit, my experienced leaders, handle the situation effectively. At last, we see the buildings of Old Shaktoolik, which indicate we are close to the checkpoint.

The dogs know straw awaits them upon arrival. A bale of straw is provided for each musher to prepare individual beds to insulate the dogs from the snow and increase their comfort. The dogs love straw, and the sight of it causes a string of barking.

“Nice day, eh?” the Shaktoolik checker says.

“Gorgeous!” I reply.

In a more serious tone, he says, “The storm will increase in intensity.”

“What are you going to do?” I ask a veteran racer and admirable musher, Paige Dronby, nervous rookie that I am, “proceed into the storm or wait it out in Shaktoolik for the next couple days?” My question is leading. I’m eager to leave Shaktoolik.

“The dogs can’t rest well at this checkpoint due to the lack of shelter from the wind,” Paige says. “If we leave soon, we might beat the worst of the storm and make it to Koyuk, which has better shelter to rest the dogs.”

I make my choice: it’s time to go. I leave with two hours of rest on the dogs. I soon regret that choice.

Leaving Shaktoolik, Paige and I put on our ice cleats and walk in front of our teams, leading them across glare ice that neither human nor dog can gain traction on.

It takes a long time to leave Shaktoolik. The winds increase harder and faster than predicted. There is no beating this storm. We struggle to see the next trail marker. I stop my sled, flip it over to act as a brake, and walk in front of the dogs to locate the stake. We continue in this fashion, crawling one trail stake to the next.

Fifteen miles out, the trail changes course to head around a spit of land. This abrupt turn is unmarked because wind and other dog teams have knocked down the trail stakes. My team can’t find the trail, and if the tracks are any proof, neither could many others. Heading toward land over a mile of glare ice, the dogs face a crosswind. Our plight changes from tough to very serious when the wind gusts—now over sixty miles per hour—blow my sled and the entire team sideways a hundred yards over the ice. I have little to no control over the situation. The conditions scare my leaders, and they can no longer guide the team. They can’t even hear my commands over the howling wind.

We are on the ice, unable to move. We crawl around the ice in circles searching for the trail. For every foot we gain in the right direction, we lose another ten. I need to reevaluate my decision to proceed to Koyuk and create a strategy that retains the greatest number of options to get my team through the night. This is now a life-threatening situation. Paige is ahead of me; her dogs travel faster than mine. No teams will leave from Shaktoolik behind us. Thoughts of the race drop away. Time to survive.

As the reality of my predicament sinks in, I think of my daughter, Amelia, who is now in sixth grade, and drown in regret and guilt over having put myself, her only living parent, in this life-or-death situation. Wet from sweat, I lead the dogs toward land inch by inch. No help is on the way. I am alone out here.

During a momentary break in the visibility, I see a shelter cabin in the distance that could offer protection from the wind. We head toward it, and I review our choices. If we make it to the cabin, we can stay there, but only for a short time because of the limited amount of dog food. Soon we will be forced back to Shaktoolik or on to Koyuk.

I worry about getting separated from the dogs. A SPOT tracker is secured to the sled bag. When triggered, it notifies international emergency services and dispatches them to our GPS location. I detach it and put it in my pocket in case I fall off the sled. Pushing the button doesn’t mean help will make it out to us, given the conditions, but it is better than nothing. I get off the sled, walk in front of the leaders, and line out the team to locate a trail stake. A wind gust pushes the sled away from me on the ice. I panic as the dogs slide farther away. I run after them. The wind pushes me with such aggression that I fall over and slam my head against the ice.

Dazed, I look around not knowing where I am. I can’t see farther than a few feet in any direction. All I can do is follow the wind and hope it leads me to the dogs. My head foggy, I stumble along until I hear barking in the distance. Is that my imagination? I alter my course until I spot the team. The dogs settled on a patch of snow solid enough to allow my overturned sled to get traction and stop.

The dogs wag their tails in enthusiasm as I walk up to the leaders. I sit there for a while hugging them, seeking to convey a confidence I don’t have. Between gusts of wind, I still see the form of the bluff where the shelter cabin is. I consider stopping here to get into my sled bag, seven feet long and two feet wide, with room to expand. Gear plus one dog can fit inside. In bad weather, I can fit myself and a few dogs in the bag but must leave the rest out in the wind.

I am drenched in sweat from the labor, but my body temperature drops as soon as I stop moving. My shivering signals the onset of hypothermia. We must keep going. The dogs need better protection. It is worth another try to make it to the shelter cabin before we resort to bagging it for the night.

After another hour, we make it to the bluff. I drive the team to the backside of the cabin and out of the wind. I walk inside to discover there is no wood for the stove, and it rips away any hope I had of drying out. What do I do? I can’t think. I have Heet for fuel, but no snow nearby to melt for water. I provide the dogs with a snack of dry commercial dog food and frozen meat, which they inhale. The back of the cabin offers little shelter for the dogs, so I take the females and the main male leader, Summit, inside the cabin. The leaders need rest to guide us through the storm into Koyuk.

The dogs outside nestle in their protective down dog coats, lick off any ice build-up, and fall asleep, while the dogs inside enjoy the break from the gang line and settle down in corners of the shelter cabin. I lay out my sleeping bag on the wood planks of the bunk bed. I have spare dry clothes, and shivering, I strip down the layers I can and swap them out. I figured packing all this extra gear was being paranoid, but you never know when you will need it. I jump into my down bag hoping to warm up. My shivering is so violent that even Ea

rs, whom I invite onto the sleeping bag, jumps off to go lay by her buddy, Summit.

I snack the dogs every couple of hours, hoping to keep their body temperatures up. I am out of my own food, having lost that bag on the ice. There is vacuum-sealed food, but without snow to melt in the metal box that serves as a cook pot, I can’t thaw it enough to eat. I better remember this lesson well. Weak from cold and hunger, I again review my options. How can we make it another forty miles to Koyuk, let alone to Nome?

With no one else to talk to, I end up in heated discourse with the wind.

“You know, there are easier ways,” I say. “Easier ways to find answers. Why don’t you tell me? Let’s make a deal. I am happy to negotiate.” My voice echoes the words back from the ice like a mirror and hits my heart with their full weight.

Over the course of my forty years, I’ve weathered my share of extreme temperatures—the baking, hundred-degree heat of that left me nauseated while competing in my first Ironman triathlon, for example—as well as other stamina challenges, including solo hiking 1,100 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail. Endurance pursuits became my way of recovering from the series of traumas that sent me wandering across the country. What I was searching for, I couldn’t always say. Escape, relief, distraction, answers, grace, a restoration of faith in the universe—at different times, these, more, and none.

My nomadic nature led me to Pompeii to dig through the remnants of the lost city, on rock climbing expeditions in Wyoming—the butte called Devils Tower and the outcrops in Vedauwoo—and at the granite pillars called the Needles in South Dakota’s Black Hills. My spiritual nature sought the energy-field vortexes in Sedona, drummed during sun dances in New Mexico, and sweated through vision quests in Arizona. At last, my wanderings took me to the home I’d envisioned for myself at ten years old: bush Alaska, the Last Frontier.

Epic Solitude

Epic Solitude